Reframing the "AI Effect"

Oct 27, 2016 · 3 minute read · Comments(This piece was originally posted on Medium)

There’s a phenomenon known as the AI effect, whereby as soon as Artificial Intelligence (AI) researchers achieve a milestone long thought to signify the achievement of true artificial intelligence, e.g., beating a human at chess, it suddenly gets downgraded to not true AI. Kevin Kelly wrote in a Wired article in October 2014:

In the past, we would have said only a superintelligent AI could drive a car, or beat a human at Jeopardy! or chess. But once AI did each of those things, we considered that achievement obviously mechanical and hardly worth the label of true intelligence. Every success in AI redefines it.

Why does this happen? Why did people once think only a superintelligent AI could beat a human at chess? Because they thought the only way that chess could be played really well was how humans play it. And humans use numerous abilities in playing chess. Surely an AI would need all those abilities too. But then along came Deep Blue: a computer that could beat any human chess player in the world, but could do absolutely nothing else. Surely this wasn’t the holy grail we had sought! Nobody would claim this was a superintelligent entity!

A superintelligent AI is also called a strong AI, an AI with human-level (or greater) intelligence. This is in contrast to weak AIs, which are focused on narrowly defined tasks, like winning chess or Go.

A better way of thinking about the AI effect is to say that tasks we previously thought would require strong AI turned out to be possible with weak AI.

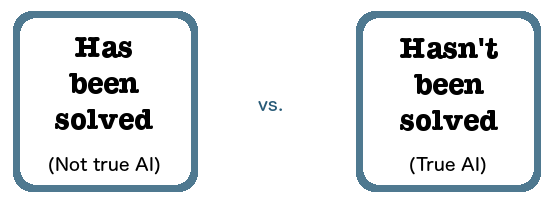

Some well-known AI researchers who note the AI effect might say “true AI is whatever hasn’t been done yet.” They distinguish between:

But this is the wrong way to frame the issue, because it makes it appear that all we need is time: if we just keep going, we’ll eventually solve everything and create strong AI. This means that every step we’re taking right now is seen as a step in that direction. I doubt many AI researchers actually believe this. It’s more like a defensive quip in the face of people’s apparent failure to be impressed enough at AI’s successes.

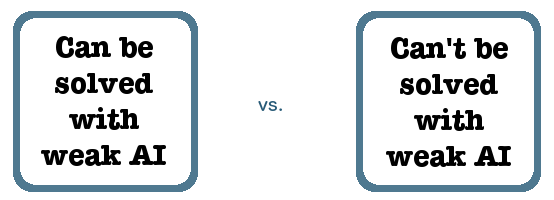

The useful distinction to make isn’t between what we’ve already solved and what we haven’t, which suggests that time is the only factor that makes a difference. Instead, the useful distinction is between:

If we frame the issue this way, then even if we originally put a problem like “build something that can beat the best human at chess” in the box on the right, because we think it would require strong AI, once we actually solve it with weak AI, we just move it to the box on the left. Note that this doesn’t imply anything at all about our progress towards building a strong AI, whereas the original framing did.

The lack of a simple progression from weak AI to strong AI has important implications. For starters, it means we can stop worrying about a Superintelligence taking over the world, as I wrote about in Why Machine Learning is not a path to the Singularity. But it also means we should focus our AI efforts, frame our research questions, and operationalize everything we do in this field with a very clear conception of the problems we should be trying to solve and how they can be formulated as weak AI problems. If they can’t, then we shouldn’t waste our time or our budgets on them.

Unless of course you’re Google, in which case you start a multi-year project which may or may not solve Natural Language Understanding. I will certainly be intrigued to follow the progress on that one!